Research

Gravitational wave search from compact binary coalescences

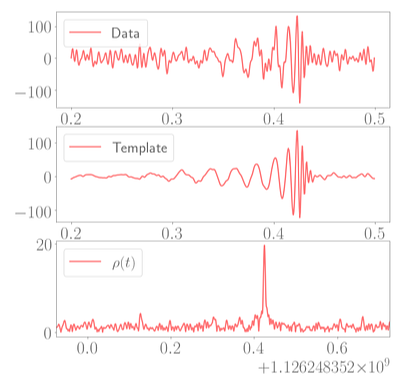

How efficiently can we detect gravitational waves observed compact binary coalescences?

Selected Publications

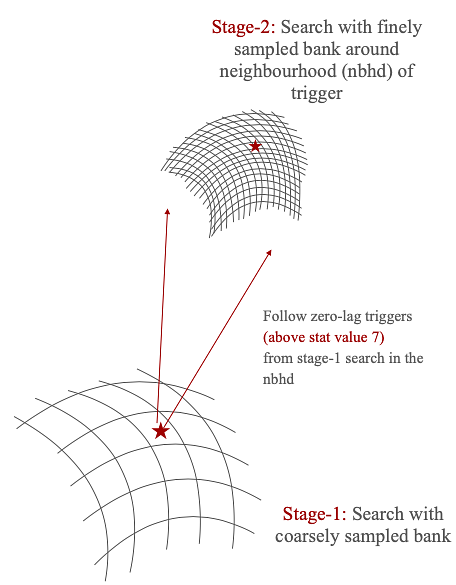

- Kanchan Soni, Alexander H. Nitz, Hierarchical searches for subsolar-mass binaries, Phys Rev D 105 064005 (2022)

- Kanchan Soni, S. Mitra, S. Dhurandhar, Statistical significance of GW signals in hierarchical search, Phys. Rev. D 109 (2024)

Primordial black holes

Can primordial black holes (PBHs) constitute a significant fraction of dark matter?

Gravitational wave observations offer a way to probe PBHs, hypothetical black holes formed from high-density fluctuations in the early universe [arXiv:1808.04771]. Unlike stellar-mass black holes, PBHs may span a broad mass range, including sub-solar scales. Detecting mergers of PBH binaries can constrain their abundance and mass distribution. Hierarchical search strategies, similar to those used for compact binaries, are particularly useful for efficiently detecting long-duration, low-mass PBH signals.

- Kanchan Soni, Alexander H. Nitz, Hierarchical searches for subsolar-mass binaries, ApJ 978 69 (2024) [arXiv:2409.11317]

Selected Publications

How Do Compact Binaries Form?

Compact binaries—such as binary black holes (BBHs) or neutron‑star binaries—can originate via multiple astrophysical pathways:

- Isolated Binary Evolution: Two massive stars evolve together, undergo mass transfer and possibly a common envelope, then both collapse to compact objects. Resulting binaries tend to have aligned spins and very low orbital eccentricity by the time they enter the detector band.

- Dynamical Formation in Dense Environments: In globular clusters or galactic nuclei, compact objects form and pair via three‑body interactions or exchanges. These binaries can retain moderate to high eccentricity and misaligned spins at formation, though gravitational radiation gradually circularises the orbit.

- Primordial Black Hole Binaries: Black holes formed in the early universe may pair via gravitational capture. These systems could exhibit a wide range of mass ratios and eccentricities, distinct from stellar‑origin binaries.

Eccentricity—the measure of how much a binary’s orbit deviates from a circle—serves as a powerful probe of formation history. Binaries formed dynamically or via capture are more likely to retain measurable eccentricity in the detector band, whereas those from isolated evolution are expected to be nearly circular. Measuring eccentricity in gravitational‑wave signals therefore helps us distinguish between formation scenarios.

In our recent study [arXiv:2508.00179], we analysed six low‑mass binary events using the new waveform model SEOBNRv5EHM (including higher‑order modes) and derived the first eccentricity constraints for several sources. We found that one event, GW200105, shows moderate evidence for eccentricity (e ≈ 0.12‑0.14 at 20 Hz), while the remaining sources are consistent with very low eccentricity (90% upper limits e ≲ 0.01–0.07). This work demonstrates how precision eccentricity measurements can trace binary formation channels and refine our astrophysical models.

Can Gravity Bend a Wave? Hunting Lensed Gravitational Signals

Strong gravitational lensing occurs when a massive object, such as a galaxy or galaxy cluster, lies along the line of sight between a gravitational wave (GW) source and the observer. The lens’s gravitational potential bends the paths of GWs, producing multiple images that arrive at Earth at different times. These time delays can range from minutes to months, depending on the lens mass and geometry.

Detecting strongly lensed GWs provides unique opportunities: multiple images of the same merger allow independent measurements of source properties, cosmological parameters, and the lensing mass distribution. Lensed events can also mimic higher-mass mergers if magnification is not accounted for, potentially biasing population studies.

How to Identify Strongly Lensed GWs:

- Consistent Waveforms: Lensed images originate from the same source, so their waveforms are nearly identical apart from amplitude and arrival time differences.

- Time Delays: Detection of multiple events with similar waveforms separated by consistent time delays can indicate lensing.

- Statistical Methods: Techniques like the χ² lens statistic can efficiently assess the likelihood that two events are lensed images of the same merger.

In our recent study [arXiv:2502.00844], we introduced a novel χ² lens statistic to efficiently identify lensed GW pairs from compact binary mergers. By comparing the phase evolution of candidate events, this method rapidly discards unlensed pairs while preserving true lensed events, offering a fast and reliable alternative to computationally expensive Bayesian analyses. Such techniques enhance our ability to find multiple images of the same merger, enabling precise tests of cosmology and gravity.

Lights, Waves, Action! Exploring the Multimessenger Universe

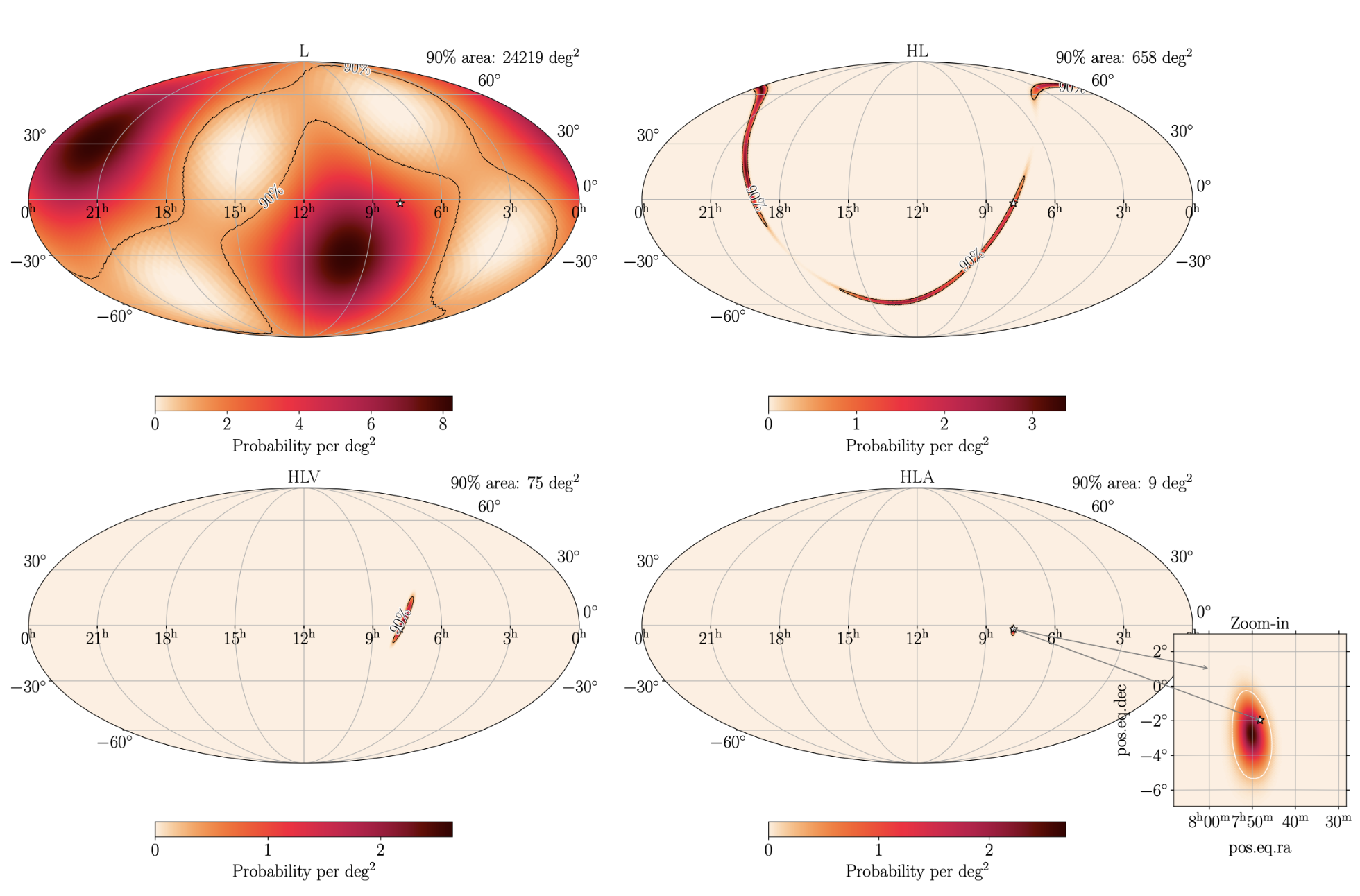

Why LIGO-India is so important?

Adding LIGO-India to the global gravitational wave network will revolutionize multimessenger astronomy. By improving sky localization for neutron star mergers, it enables rapid follow-up with telescopes to detect electromagnetic counterparts like kilonovae. In our recent work [arXiv:2409.11361] we showed that LIGO-India could double the number of BNS mergers with identified EM signals and dramatically speed up constraints on the Hubble constant, making the universe’s expansion more precisely measurable.